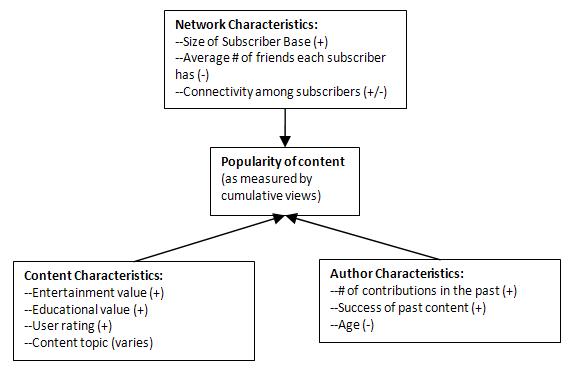

Last time I discussed a few research findings on what makes people pass on information to others. This week, I would like to follow up on the topic and talk about a recent project done by Zsolt Katona (@UC Berkley) and his colleagues. The research question Katona and colleagues set out to answer is what drives the growth of an online community. They surmised that the specific social network structure of the initial adopters affect the adoption likelihood of subsequent followers. To test their thinking, the researchers analyzed the first 3.5 years of data from a central-European social networking website, when no marketing activities had been engaged to promote the site and the network had been growing organically through word-of-mouth. Here is the gist of what they found.

People do tend to follow the crowd but a more closely-knit crowd carries much more power

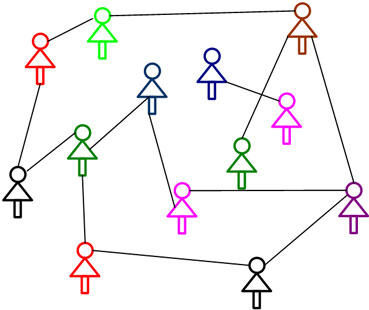

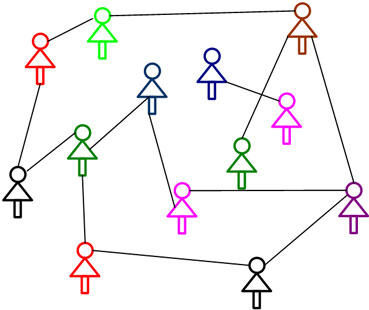

We all have hesitations when it comes to novel new things and may consider them risky. Depending on how risk averse we are, we may wait until some or a majority of other people have adopted the new thing before we jump onto the wagon. In my own research project documented in the last blog, we found the median adoption threshold to be 50%, incidentally supporting the “majority rules” mentality. But the threshold reported by our sample ranged across the whole spectrum from 0% to 100%. Consistent with this idea of an adoption threshold, Katona and colleagues found that more people in one’s social circle adopting a social network makes one more likely to join the network. In this context, perhaps an additional driver besides risk is the fact that the utility of a network increases when more of one’s friends belong to it. The story does not stop here, however. The researchers also found that a closely-knit (or high-density in network science terminology) network where everyone knows everyone else is much more influential. If the same number of individuals in a closely-knit network joins a social network, the remaining non-adopters are much more likely to follow suit than if it were a loose (low density) network of sorts.

Social butterflies are not the most influential

In network science, the fact that some individuals have way more friends/connections than most others in the same network has often been compared to the rich get richer phenomenon. But unlike the richer people who do have solid cash to spend, social butterflies who have tons of friends (think 1000+ or even 500+ Facebook friends) are actually quite weak when it comes to influencing other people’s opinions. Well, at least when it comes to the decision to join a social network any way. This may be surprising on first look. But not so when one thinks deeper about human psychology. We all have limited energy to build and maintain friendships. The more friends we accumulate on a regular basis, the less energy we have to develop a deep and meaningful relationship with each individual, and thus the less we are able to exert a strong influence.

Weak ties may be good for information travel but exert limited influence

The strength of the weak tie has been a well-known phenomenon for more than 20 years, referring to the fact that weak ties that link disconnected networks are critical to the spreading of information. However, for exactly the same reason, the central role played by these weak ties also makes a network formed around such ties more vulnerable. Referring to these individuals as structural holes, Katona and colleagues found that the adoption of a social network by these structural holes has less of an impact on their friends, perhaps accurately reflecting the fact that these are “weak” ties.

Lessons learned

- Many factors create counter effects when it comes to increasing awareness of a community vs. increasing participation in a community.

- While sometimes it may be necessary to target loosely-knit networks (more weak ties) for increasing the awareness of your online community, closely knit networks are eventually critical to increasing actual participation in your community.

- The same thing goes with highly-connected individuals. While those who have lots of friends may be good for getting the word out, individuals who have a more moderate friend circle may be more ideal for building the community.

- For a business, how these counter effects should balance out will depend on the exact goal for the online community at each stage.

Reference

Zsolt Katona, Peter Pal Zubcsek, and Miklos Sarvary (2009), “Network Effects and Personal Influences: Diffusion of an Online Social Network“. The full paper can be downloaded from Katona’s website at http://www.cs.bme.hu/~zskatona/pdf/diff.pdf