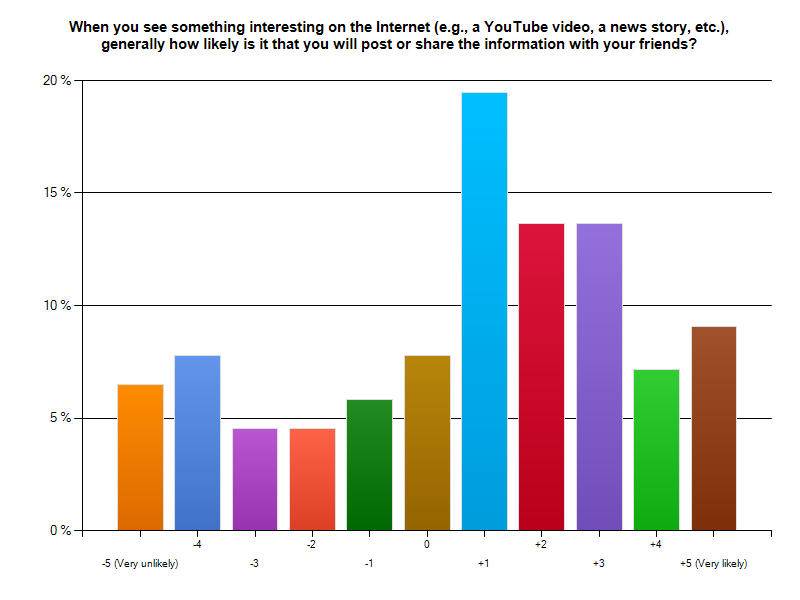

If you are involved in social media or viral marketing, most likely you have wondered how to increase the passing-along of your viral content. My co-author Michelle Rogerson and I have been wondering about the same question too in our research project on the spreading of user-generated content online. As the starting point, we conducted an exploratory survey to find out people’s general tendency to share information online and what makes them more or less likely to share information with others. Using snowballing technique, we were able to gather responses from 156 Internet users. These users’ ages ranged from 18 to 62 with a median age of 30. 46% of these users were males and 54% were females. Here I share with you some key findings from the survey.

“If my friend shares something with me, I will view it. But don’t really expect me to pass it on.”

We asked our respondents how likely they are to view information shared by someone they know, and over 60% of them agreed that it is quite likely (7 or higher on a 10-point scale). This is good news because in the case of viral campaigns, encouraging people to share information with their friends is likely to increase the reach of the campaign. The bad news we found, however, is that way fewer of them would further pass on the information to their respective friends. Less than 20% of them said they are likely to pass on information shared with them by their friends. Interestingly, when asked the same question about information consumers found online themselves rather than shared by their friends, those who selected likely to pass on information increased to about 30%. The lesson here is that first-order word-of-mouth (consumers passing on information they found themselves) is more likely to happen than second-order word-of-mouth (consumers passing on information that are found by their friends). Therefore, companies engaging in word-of-mouth campaigns should still try to spread the word to as many “seeds” as possible rather than counting on a few starting points.

“Make me believe that the information is relevant to my friends and I will pass it on.”

The survey contained an open-ended question asking the respondents to list the factors that would make them more likely to share information online. The dominant reason listed (by 35% of the sample) was relevance to the friends that they are passing the information on to. This is perhaps not surprising considering that few of us want to jam our friends’ inbox with junk information. For companies, this means an opportunity to encourage passing-along by demonstrating the content’s relevance to a consumer’s social circle. Financial incentives offered to friends by some referral programs is an example of this approach. The second most widely listed reason was something funny. Apparently, we as human beings like to share laughter with others. Below are the top five reasons the respondents cited ranked by frequency:

- Relevance to those sharing information with

- Humor

- Relevance to oneself

- Importance/worthiness of information

- Unusual/unique information

![]()

Opinion leaders share more information but are also more likely to seek advice.Studying information sharing is not complete without considering opinion leaders, those individuals that are on the cutting edge and are likely to influence other people’s opinions. We found that being an opinion leader increases the likelihood to share information with others by 38%, perhaps partially explaining why these people are opinion leaders in the first place. While this finding seems rather obvious, what is not so obvious is the finding that opinion leaders are also more likely to seek advice from others such as family, friends, and neighbors. Compared with regular individuals, opinion leaders are 25% more likely to seek advice from others. This finding is important because we have often seen the argument that the right way to treat social media is to be social (in other words, interacting with others). Our study finds concrete support for that. A true opinion leader does not just broadcast information to others but also listens closely and actively seeks out others’ feedback.

As we move forward to the next stage of the research project, we would love to hear your thoughts. What makes you more likely to share stuff with other people? As a company, how do you manage your viral campaign content and seeding process so that it can create the maximum ripple effect?