In between the wedding and my race against the clock to get as much research done as possible before my research leave is over in January, the year 2009 has quietly slipped away and the holiday season is already upon us. First of all, happy holidays! As a gift to my readers, I want to bring some new exciting research insights from the conference The Emergence and Impact of User-Generated Content (UGC) I just attended in Philadelphia last week. The conference was co-hosted by the Wharton Interactive Media Institute and the Marketing Science Institute, and featured top-notch researchers and practitioners who work in the field of social media and UGC.

A major question addressed by quite a few presentations at the conference was the impact of user-generated content. So in Part I of this two-part conference report series, I would like to highlight three presentations that I found particularly interesting with regard to this topic.

Does consumer chatter about a product affect stock return?

The answer is yes, according to the research presented by Professor Gerard Tellis from the University of Southern California. In their research, Professor Tellis and his doctoral student Seshadri Tirunillai looked at six diverse product categories with rich consumer reviews: data storage, footwear, toys, personal computers, cellphones, and PDAs/smartphones. They gathered consumer reviews in these product categories from three sources: Amazon.com, Epinions.com, and Yahoo! Shopping. These reviews were then analyzed for the overall rating, review volume, and valence (positive or negative) of review associated with each product. Using a mathematical approach called vector autoregressive, the researchers tied these review characteristics to each company’s stock return and volatility. They found that consumer reviews lead stock performance by a few weeks (meaning that consumer reviews can help predict stock performance a few weeks ahead). Specifically, the volume of review (after controlling for the valence of review) has a positive effect on stock return. The overall rating (e.g., 3.5 out of 5) did not have any significant impact on stock performance. But the number of negative reviews and the average percent of negative expressions in the reviews negatively impact stock return and increase stock volatility. In contrast, positive reviews did not have a significant impact.

Lessons for marketers:

- It is justifiable not only from a marketing perspective to monitor consumer opinions in social media but it makes financial sense as well. Research such as this can help make an argument to financial managers why a company should invest in such monitoring activities.

- Although positive reviews may make one feel warm and fuzzy, it’s much more important to pay attention to negative reviews. In general, negative information is much more diagnostic in conveying market sentiment.

Lessons for investors:

- Consumer reviews may seem far removed from the complex mathematical modeling that goes into stock picking and performance prediction. But this research suggests the value for investors to monitor this social space.

- The researchers further recommended a few investment approaches. For example, as a short-term strategy, buy a stock when its product review enters top 20% and sell the stock when it drops out of the top 20%. The recommended holding period for this strategy is 6 weeks.

Do bloggers affect product sales?

Bloggers like me probably would all like to know that we are making a real impact after the time and effort we’ve put into our blogs. Some companies also invest heavily in the blogosphere and want to know whether that’s a wise thing to do. The research presented by Professor Sriram Venkataraman from Emory University found that blogger influence is geographic-specific depending on the demographics of a market. Using movie industry data, this research finds that a movie’s first-day national sales is not associated with blog variables. However, when looking from the DMA (designated market area) level, strong geographic influence emerges. Not surprisingly, markets with a larger portion of young people are more likely to be affected by blogs and at the same time are more likely to discount the influence of company-sponsored advertising. For markets with a higher proportion of female consumers, the research found that they tend to be more forgiving to negative blogs. These consumers could read quite negative blogs about a movie but still feel and act positively toward the movie.

Lessons for marketers:

- Consumer blogs can be a worthwhile tool to integrate into a company’s marketing strategy.

- Selectively using these tools based on each market’s demographics may be more effective than a blanket strategy.

What about user contribution in new product development?

This research first struck me as using a very clever data source to address an important question. Partially based on Professor Matthew O’Hern’s doctoral dissertation, this project uses the well-known open source community SourceForge.net to examine if user collaboration and contribution truly lead to better and faster product development. The answer is mixed. O’Hern and colleagues classified user contributions on SourceForget into three categories: (1) user reports: reports of bugs and issues found in a piece of software; (2) user requests: requests of new functionality or modifications to be added to future software releases; (3) user revisions: user-submitted solutions (i.e., codes) for fixing certain problems or adding new functionality to a software release. They found that:

- User reports of problems increase release activities, indicating a positive impact on software development.

- At the same time, such problem reports alert other users of issues with the software and reduce the download volume for a software release.

- User requests have the most negative impact, both reducing download volume and release activities.

- Most surprising to me, users submitting their own solutions did not have any significant impact on release activities. The only impact it had was on increasing download amount for a given month.

Lessons for marketers:

- Wiki-type efforts by users may not always be beneficial to a company’s new product development. When not properly managed, it can actually prolong the development process and reduce the speed-to-market.

- Caveat: SourceForge is a community of mostly volunteers who do not have a strong commercial interest. Therefore, the proper utilization and integration of user revisions may be limited due to the lack of human power and resources. I would not be surprised that user submission will have a more positive impact in a more closely managed environment.

* * * * * * *

Plenty of information to digest for a while. So I’m gonna stop here for Part I of the series. What do you think of these research insights? I’d love to hear back from you. If you find any of these projects particularly interesting and would like more information, I encourage you to contact the presenter. Whenever possible, I tried to provide a link to the presenter’s homepage so that you can find his/her contact information.

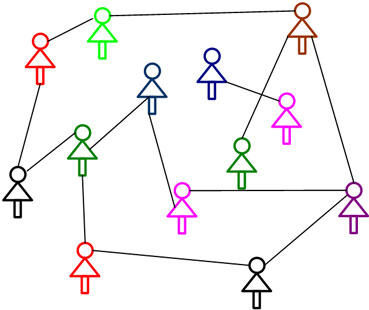

In Part II of this series, I will discuss another project on a privacy-friendly target advertising approach based on social network data. I will also share with you a few high-priority topics related to social media and Internet marketing that were identified by practitioners at the conference. So stay tuned!